Part 2. How to Manage Your Infrastructure as Code

Update, June 25, 2024: This blog post series is now also available as a book called Fundamentals of DevOps and Software Delivery: A hands-on guide to deploying and managing software in production, published by O’Reilly Media!

This is Part 2 of the Fundamentals of DevOps and Software Delivery series. In Part 1, you learned how to deploy your app using PaaS and IaaS, but it required a lot of manual steps clicking around a web UI. This is fine while you’re learning and experimenting, but if you manage everything at a company this way—what’s sometimes called ClickOps—it quickly leads to problems:

- Deployments are slow and tedious

-

You can’t deploy too often or respond to problems or opportunities too quickly.

- Deployments are error-prone and inconsistent

-

You end up with lots of bugs, outages, and late-night debugging sessions. You become fearful and slow to introduce new features.

- Only one person knows how to deploy

-

That person is overloaded and never has time for long-term improvements. If they were to leave or get hit by a bus, everything would grind to a halt.[5]

Fortunately, these days, there is a better way to do things: you can manage your infrastructure as code (IaC). Instead of clicking around manually, you use code to define, deploy, update, and destroy your infrastructure. This represents a key insight of DevOps: most tasks that you used to do manually can now be automated using code, as shown in Table 5.

| Task | How to manage as code | Example | Part |

|---|---|---|---|

Provision servers |

Provisioning tools |

Use OpenTofu to deploy a server |

This blog post |

Configure servers |

Server templating tools |

Use Packer to create an image of a server |

This blog post |

Configure apps |

Configuration files and services |

Read configuration from a JSON file |

|

Configure networking |

Software-defined networking |

Use Istio as a service mesh |

|

Build apps |

Build systems |

Build your app with NPM |

|

Test apps |

Automated tests |

Write automated tests using Jest |

|

Deploy apps |

Automated deployment |

Do a rolling deployment with Kubernetes |

|

Scale apps |

Auto scaling |

Set up auto scaling policies in AWS |

|

Recover from outages |

Auto healing |

Set up liveness probes in Kubernetes |

|

Manage databases |

Schema migrations |

Use Knex.js to update your database schema |

|

Test for compliance |

Policy as code |

Check compliance using Open Policy Agent |

If you search around, you’ll quickly find that there are many tools out there that allow you to manage your infrastructure as code, including Chef, Puppet, Ansible, Pulumi, Terraform, OpenTofu, CloudFormation, Docker, Packer, and so on. Which one should you use? Many of the comparisons you find online between these tools do little more than list the general properties of each tool and make it sound like you could be equally successful with any of them. And while that’s true in theory, it’s not true in practice. There are considerable differences between these tools, and your odds of success go up significantly if you know how to pick the right tool for the job.

This blog post will help you navigate the IaC space by introducing you to the four most common categories of IaC tools:

-

Ad hoc scripts: e.g., use a Bash script to deploy a server.

-

Configuration management tools: e.g., use Ansible to deploy a server.

-

Server templating tools: e.g., use Packer to build an image of a server.

-

Provisioning tools: e.g., Use OpenTofu to deploy a server.

You’ll work through examples where you deploy the same infrastructure using each of these approaches, which will allow you to see how different IaC categories perform across a variety of dimensions (e.g., verbosity, consistency, scale, and so on), so that you can pick the right tool for the job.

Note that this blog post focuses on tools for managing infrastructure, whereas the next post focuses on tools for managing apps. These two domains have a lot of overlap, as you deploy infrastructure to run apps, and you may even deploy those apps using IaC tools (you’ll see examples of just that in this blog post). However, as you’ll see, there are key differences between the infrastructure domain, where you use IaC tools such as OpenTofu to configure servers, load balancers, and networks, and the app domain, where you use orchestration tools such as Kubernetes to handle scheduling, auto scaling, auto healing, and service communication.

Before digging into the details of various IaC tools, it’s worth asking, why bother? Learning and adopting new tools has a cost, so what are the benefits of IaC that make this worthwhile? This is the focus of the next section.

The Benefits of IaC

When your infrastructure is defined as code, you are able to use a wide variety of software engineering practices to dramatically improve your software delivery processes, including the following:

- Speed and safety

-

Instead of a person doing deployments manually, which is slow and error-prone, defining your infrastructure as code allows a computer to carry out the deployment steps, which will be significantly faster and more reliable.

- Documentation

-

If your infrastructure is defined as code, then the state of your infrastructure is in source files that anyone can read, rather than locked away in a single person’s head. In other words, IaC acts as a form of documentation, allowing everyone in the organization to understand how things work.

- Version control

-

Storing your IaC source files in version control (which you’ll do in Part 4) makes it easier to collaborate on your infrastructure, debug issues (e.g., by checking the version history to find out what changed), and to resolve issues (e.g., by reverting back to a previous version).

- Validation

-

If the state of your infrastructure is defined in code, for every single change, you can perform a code review, run a suite of automated tests, and pass the code through static analysis tools—all practices that are known to significantly reduce the chance of defects (you’ll see examples of all of these practices in Part 4).

- Self-service

-

If your infrastructure is defined in code, developers can kick off their own deployments, instead of relying on others to do it.

- Reuse

-

You can package your infrastructure into reusable modules so that instead of doing every deployment for every product in every environment from scratch, you can build on top of known, documented, battle-tested pieces.

- Happiness

-

There is one other important, and often overlooked, reason for why you should use IaC: happiness. Manual deployments are repetitive and tedious. Most people resent this type of work, since it involves no creativity, no challenge, and no recognition. You could deploy code perfectly for months, and no one will take notice—until that one day when you mess it up. IaC offers a better alternative that allows computers to do what they do best (automation) and developers to do what they do best (creativity).

Now that you have a sense of why IaC is so valuable, in the following sections, you’ll explore the most common categories of IaC tools, starting with ad hoc scripts.

Ad Hoc Scripts

The first approach you might think of for managing your infrastructure as code is to use an ad hoc script. You take whatever task you were doing manually, break it down into discrete steps, and use your favorite scripting language (e.g., Bash, Ruby, Python) to capture each of those steps in code. When you run that code, it can automate the process of creating infrastructure for you. The best way to understand this is to try it out, so let’s go through an example of an ad hoc script written in Bash.

Example: Deploy an EC2 Instance Using a Bash Script

|

Example Code

As a reminder, you can find all the code examples in the blog post series’s sample code repo in GitHub. |

As an example, let’s create a Bash script that automates all the manual steps you did in Part 1 to deploy a simple Node.js app in AWS. Head into the fundamentals-of-devops folder you created in Part 1 to work through the examples in this blog post series, and create a new subfolder for this part and the Bash script:

$ cd fundamentals-of-devops

$ mkdir -p ch2/bashCopy the exact same user data script from Part 1 into a file called user-data.sh within the ch2/bash folder:

$ cp ch1/ec2-user-data-script/user-data.sh ch2/bash/Next, create a Bash script called deploy-ec2-instance.sh, with the contents shown in Example 3:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

set -e

export AWS_DEFAULT_REGION="us-east-2"

user_data=$(cat user-data.sh)

(1)

security_group_id=$(aws ec2 create-security-group \

--group-name "sample-app" \

--description "Allow HTTP traffic into the sample app" \

--output text \

--query GroupId)

(2)

aws ec2 authorize-security-group-ingress \

--group-id "$security_group_id" \

--protocol tcp \

--port 80 \

--cidr "0.0.0.0/0" > /dev/null

(3)

image_id=$(aws ec2 describe-images \

--owners amazon \

--filters 'Name=name,Values=al2023-ami-2023.*-x86_64' \

--query 'reverse(sort_by(Images, &CreationDate))[:1] | [0].ImageId' \

--output text)

(4)

instance_id=$(aws ec2 run-instances \

--image-id "$image_id" \

--instance-type "t2.micro" \

--security-group-ids "$security_group_id" \

--user-data "$user_data" \

--tag-specifications 'ResourceType=instance,Tags=[{Key=Name,Value=sample-app}]' \

--output text \

--query Instances[0].InstanceId)

public_ip=$(aws ec2 describe-instances \

--instance-ids "$instance_id" \

--output text \

--query 'Reservations[*].Instances[*].PublicIpAddress')

(5)

echo "Instance ID = $instance_id"

echo "Security Group ID = $security_group_id"

echo "Public IP = $public_ip"If you’re not an expert in Bash syntax, all you have to know about this script is that it uses the AWS Command Line Interface (CLI) to automate the exact steps you did manually in the AWS console in Part 1:

| 1 | Create a security group. |

| 2 | Update the security group to allow inbound HTTP requests on port 80. |

| 3 | Look up the ID of the Amazon Linux AMI. |

| 4 | Deploy an EC2 instance that will run the Amazon Linux AMI from (3), on a t2.micro instance, with the security group

from (1), the user data script from user-data.sh, and the Name tag set to "sample-app." |

| 5 | Output the IDs of the security group and EC2 instance and the public IP of the EC2 instance. |

|

Watch out for snakes: these are simplified examples for learning, not for production

The examples in this blog post are still simplified for learning and not suitable for production usage, due to the security concerns and user data limitations explained in Watch out for snakes: these examples have several problems. You’ll see how to resolve these limitations in the next blog post. |

If you want to run the script, you first need to give it execute permissions:

$ cd ch2/bash

$ chmod u+x deploy-ec2-instance.shNext, install the AWS CLI (minimum version 2.0), authenticate to AWS, and run the script as follows:

$ ./deploy-ec2-instance.sh

Instance ID = i-0335edfebd780886f

Security Group ID = sg-09251ea2fe2ab2828

Public IP = 52.15.237.52After the script finishes, give the EC2 instance a minute or two to boot up, and then try opening up

http://<Public IP> in your web browser, where <Public IP> is the IP address the script outputs at the end.

You should see:

Hello, World!

Congrats, you are now running your app using an ad hoc script!

|

Get your hands dirty

Here are a few exercises you can try at home to go deeper:

|

When you’re done experimenting with this script, you should manually undeploy the EC2 instance as shown in Figure 9. This ensures that your account doesn’t start accumulating any unwanted charges.

You’ve now seen one way to manage your infrastructure as code. Well, sort of. This script, and most ad hoc scripts, have quite a few drawbacks in terms of using them to manage infrastructure, as discussed in the next section.

How Ad Hoc Scripts Stack Up

Below is a list of criteria, which I’ll refer to as the IaC category criteria, that you can use to compare different categories of IaC tools. In this section, I’ll flush out how ad hoc scripts stack up according to the IaC category criteria; in later sections, you’ll see how the other IaC categories perform along the same criteria, giving you a consistent way to compare the different options.

- CRUD

-

CRUD stands for create, read, update, and delete. To manage infrastructure as code, you typically need support for all four of these operations, whereas most ad hoc scripts only handle one: create. For example, this script can create a security group and EC2 instance, but if you run this script a second or third time, the script doesn’t know how to "read" the state of the world, so it has no awareness that the security group and EC2 instance already exist, and will always try to create new infrastructure from scratch. Likewise, this script has no built-in support for deleting any of the infrastructure it creates (which is why you had to terminate the EC2 instance manually). So while ad hoc scripts make it faster to create infrastructure, they don’t really help you manage it.

- Scale

-

Solving the CRUD problem in an ad hoc script for a single EC2 instance is hard enough, but a real architecture may contain hundreds of instances, plus databases, load balancers, networking configuration, and so on. There’s no easy way to scale up scripts to keep track of and manage so much infrastructure.

- Deployment strategies

-

In real-world architectures, you typically need to use various deployment strategies to roll out updates, such as rolling deployments and blue-green deployments (you’ll learn more about deployment strategies in Part 5). With ad hoc scripts, you’d have to write the logic for each deployment strategy from scratch.

- Idempotency

-

To manage infrastructure, you typically want code that is idempotent, which means it’s safe to re-run multiple times, as it will always produce the same effect as if you ran it once. Most ad hoc scripts are not idempotent. For example, if you ran the Bash script once, and it created the security group and EC2 instance, and then you ran the script again, it would try to create another security group and EC2 instance, which is probably not what you want, and would also lead to an error, as you can’t have two security groups with the same name.

- Consistency

-

The great thing about ad hoc scripts is that you can use any programming language you want, and you can write the code however you want. The terrible thing about ad hoc scripts is that you can use any programming language you want, and you can write the code however you want. I wrote the Bash script one way; you might write it another way; your coworker may choose a different language entirely. If you’ve ever had to maintain a large repository of ad hoc scripts, you know that it almost always devolves into a mess of unmaintainable spaghetti code. As you’ll see shortly, tools that are designed specifically for managing infrastructure as code often provide a single, idiomatic way to solve each problem, so that your codebase tends to be more consistent and easier to maintain.

- Verbosity

-

The Bash script to launch a simple EC2 instance, plus the user data script, add up to around 80 lines of code—and that’s without the code for CRUD, deployment strategies, and idempotency. An ad hoc script that handles all of these properly would be many times longer. And we’re talking about just one EC2 instance; your production infrastructure may include hundreds of instances, plus databases, load balancers, network configurations, and so on. The amount of custom code it takes to manage all of this with ad hoc scripts quickly becomes untenable. As you’ll see shortly, tools that are designed specifically for managing infrastructure as code typically provide APIs that are more concise for accomplishing common infrastructure tasks.

Ad hoc scripts have always been, and will always be, a big part of software delivery. They are the glue and duct tape of the DevOps world. However, they are not the best choice as a primary tool for managing infrastructure as code.

|

Key takeaway #1

Ad hoc scripts are great for small, one-off tasks, but not for managing all your infrastructure as code. |

If you’re going to be managing all of your infrastructure as code, you should use an IaC tool that is purpose-built for the job, such as one of the ones discussed in the next several sections.

Configuration Management Tools

After trying out ad hoc scripts, and hitting all the issues mentioned in the previous section, the software industry moved on to configuration management tools, such as Chef, Puppet, and Ansible (full list). These tools first started to appear before cloud computing was ubiquitous, so the way they were originally designed was to assume someone else had done the work of setting up the hardware (e.g., your Ops team racked the servers in your own data center), and the primary purpose of these tools was to handle the software, including configuring the operating system, installing dependencies, deploying and updating apps, and so on.

Each configuration management tool has you write code in a different domain specific language (DSL). For example, with Chef, you write code in a DSL built on top of Ruby, whereas with Ansible, you write code in a DSL built on top of YAML. Once you’ve written the code, most configuration management tools work to update your servers to match the desired state in your code. In order to update your servers, configuration management tools rely on the following two items:

- Master servers

-

You run one or more master servers (Chef Server, Puppet Server, or Ansible Automation Controller[6]), which are responsible for communicating with the rest of your servers, tracking the state of those servers, providing a central UI and API to manage those servers, and running a reconciliation loop that continuously ensures the configuration of each server matches your desired configuration.

- Agents

-

Chef and Puppet require you to install custom agents (Chef Client and Puppet Agent) on each server, which are responsible for connecting to and authenticating with the master servers. You can configure the master servers to either push changes to these agents, or to have the agents pull changes from the master servers. Ansible, on the other hand, pushes changes to your servers over SSH, which is pre-installed on most Linux/Unix servers by default (you’ll learn more about SSH in Part 7). Whether you rely on agents or SSH, this leads to a chicken-and-egg problem: in order to be able to configure your servers (with configuration management tools), you first have to configure your servers (install agents or set up SSH authentication). Solving this chicken-and-egg problem usually requires either manual intervention or additional tools.

The best way to understand configuration management is to see it in action, so let’s go through an example of using Ansible.

Example: Deploy an EC2 Instance Using Ansible

To be able to use configuration management, the first thing you need is a server. This section will show you how to deploy an EC2 instance using Ansible. Note that deploying and managing servers (hardware) is not really what configuration management tools were designed to do—later in this blog post, you’ll see how provisioning tools are typically a better fit for this task—but for spinning up a single server for learning and testing, Ansible is good enough.

Create a new folder called ansible:

$ cd fundamentals-of-devops

$ mkdir -p ch2/ansible

$ cd ch2/ansibleInside the Ansible folder, create an Ansible playbook called create_ec2_instances_playbook.yml, with the contents shown in Example 4:

- name: Deploy EC2 instances in AWS

hosts: localhost (1)

gather_facts: no

environment:

AWS_REGION: us-east-2

vars: (2)

num_instances: 1

base_name: sample_app_ansible

http_port: 8080

tasks:

- name: Create security group (3)

amazon.aws.ec2_security_group:

name: "{{ base_name }}"

description: "{{ base_name }} HTTP and SSH"

rules:

- proto: tcp

ports: ["{{ http_port }}"]

cidr_ip: 0.0.0.0/0

- proto: tcp

ports: [22]

cidr_ip: 0.0.0.0/0

register: aws_security_group

- name: Create a new EC2 key pair (4)

amazon.aws.ec2_key:

name: "{{ base_name }}"

file_name: "{{ base_name }}.key" (5)

no_log: true

register: aws_ec2_key_pair

- name: 'Get all Amazon Linux AMIs' (6)

amazon.aws.ec2_ami_info:

owners: amazon

filters:

name: al2023-ami-2023.*-x86_64

register: amazon_linux_amis

- name: Create EC2 instances with Amazon Linux (7)

loop: "{{ range(num_instances | int) | list }}"

amazon.aws.ec2_instance:

name: "{{ '%s_%d' | format(base_name, item) }}"

key_name: "{{ aws_ec2_key_pair.key.name }}"

instance_type: t2.micro

security_group: "{{ aws_security_group.group_id }}"

image_id: "{{ amazon_linux_amis.images[-1].image_id }}"

tags:

Ansible: "{{ base_name }}" (8)An Ansible playbook specifies the hosts to run on, some variables, and then a list of tasks to execute on those hosts. Each task runs a module, which is a unit of code that can execute various commands. The preceding playbook does the following:

| 1 | Specify the hosts: The hosts entry specifies where this playbook will run. Most playbooks run on remote hosts

(on servers you’re configuring), as you’ll see in the next section, but this playbook runs on localhost, as it

is just making a series of API calls to AWS to deploy a server. |

| 2 | Define variables: The vars block defines three variables used throughout the playbook: num_instances, which

specifies how many EC2 instances to create (default: 1); base_name, which specifies what to name all the

resources created by this playbook (default: "sample_app_ansible"); and http_port, which specifies the port the

instances should listen on for HTTP requests (default: 8080). In this blog post, you’ll use the

default values for all of these variables, but in Part 3, you’ll see how to override these

variables. |

| 3 | Create a security group: The first task in the playbook uses the amazon.aws.ec2_security_group module to

create a security group in AWS. The preceding code configures this security group to allow inbound HTTP requests on

http_port and inbound SSH requests on port 22. Note the use of Jinja

templating syntax, such as {{ base_name }} and {{ http_port }}, to dynamically fill in the values of the

variables defined in (1). |

| 4 | Create an EC2 key pair: An EC2 key pair is a public/private key pair that can be used to authenticate to an EC2 instance over SSH. |

| 5 | Save the private key: Store the private key of the EC2 key pair locally in a file called {{ base_name }}.key,

which with the default variable values will resolve to sample_app_ansible.key. You’ll use this private key in the

next section to authenticate to the EC2 instance. |

| 6 | Look up the ID of the Amazon Linux AMI: Use the ec2_ami_info module to do the same lookup you saw in the Bash

script with aws ec2 describe-images. |

| 7 | Create EC2 instances: Create one or more EC2 instances (based on the num_instances variable) that run Amazon

Linux and use the security group and public key from the previous steps. |

| 8 | Tag the instance: This sets the Ansible tag on the instance to {{ base_name }}, which will default to

"sample_app_ansible." You’ll use this tag in the next section. |

To run this Ansible playbook, install Ansible (minimum version 2.17), authenticate to AWS, and run the following:

$ ansible-playbook -v create_ec2_instances_playbook.ymlWhen the playbook finishes running, you should have a server running in AWS. Now you can see what configuration management tools are really designed to do: configure servers to run software.

Example: Configure a Server Using Ansible

In order for Ansible to be able to configure your servers, you have to provide an inventory, which is a file that specifies which servers you want configured, and how to connect to them. If you have a set of physical servers on-prem, you can put the IP addresses of those servers in an inventory file, as shown in Example 5:

webservers:

hosts:

10.16.10.5:

10.16.10.6:

dbservers:

hosts:

10.16.20.3:

10.16.20.4:

10.16.20.5:The preceding file organizes your servers into groups: the webservers group has two servers in it and the

dbservers group has three servers. You’ll then be able to write Ansible playbooks that target the hosts in

specific groups.

If you are running servers in the cloud, where servers come and go often, and IP addresses change frequently,

you’re better off using an inventory plugin that can dynamically discover your servers. For example, you can use the

aws_ec2 inventory plugin to discover the EC2 instance you deployed in the previous section. Create a file called

inventory.aws_ec2.yml with the contents shown in Example 6:

plugin: amazon.aws.aws_ec2

regions:

- us-east-2

keyed_groups:

- key: tags.Ansible (1)

leading_separator: '' (2)This code does the following:

| 1 | Create groups based on the Ansible tag of the instance. In the previous section, you set this tag

to "sample_app_ansible," so that will be the name of the group. |

| 2 | By default, Ansible adds a leading underscore to group names. This disables it so the group name matches the tag name. |

For each group in your inventory, you can specify group variables to configure how to connect to the servers in that group. You define these variables in YAML files in the group_vars folder, with the name of the file set to the name of the group. For example, for the EC2 instance in the sample_app_ansible group, you should create a file in group_vars/sample_app_ansible.yml with the contents shown in Example 7:

ansible_user: ec2-user (1)

ansible_ssh_private_key_file: sample_app_ansible.key (2)

ansible_host_key_checking: false (3)The group variables this file defines are:

| 1 | Use "ec2-user" as the username to connect to the EC2 instance. This is the username you need to use with Amazon Linux AMIs. |

| 2 | Use the private key at sample_app_ansible.key to authenticate to the instance. This is the private key the playbook saved in the previous section. |

| 3 | Skip host key checking so you don’t get interactive prompts from Ansible. |

Alright, with the inventory stuff out of the way, you can now create a playbook to configure your server to run the Node.js sample app. Create a file called configure_sample_app_playbook.yml with the contents shown in Example 8:

- name: Configure the EC2 instance to run a sample app

hosts: sample_app_ansible (1)

gather_facts: true

become: true

roles:

- sample-app (2)This playbook does two things:

| 1 | Target the servers in the sample_app_ansible group, which should be a group with the EC2 instance you deployed in the previous section. |

| 2 | Configure the servers using an Ansible role called sample-app, as discussed next. |

An Ansible role defines a logical profile of an application in a way that promotes modularity and code reuse. Ansible roles also provide a standardized way to organize tasks, templates, files, and other configuration as per the following folder structure:

roles

└── <role-name>

├── defaults

│ └── main.yml

├── files

│ └── foo.txt

├── handlers

│ └── main.yml

├── tasks

│ └── main.yml

├── templates

│ └── foo.txt.j2

└── vars

└── main.yml

Each folder has a specific purpose: e.g., the tasks folder defines tasks to run on a server; the files folder has files to copy to the server; the templates folder lets you use Jinja templating to dynamically fill in data in files; and so on. Having this standardized structure makes it easier to navigate and understand an Ansible codebase.

To create the sample-app role for this playbook, create a roles/sample-app folder in the same directory as

configure_sample_app_playbook.yml:

.

├── configure_sample_app_playbook.yml

├── group_vars

├── inventory.aws_ec2.yml

└── roles

└── sample-app

├── files

│ └── app.js

└── tasks

└── main.yml

Within roles/sample-app, you should create files and tasks subfolders, which are the only parts of the standardized role folder structure you’ll need for this simple example. Copy the Node.js sample app from Part 1 into files/app.js:

$ cp ../../ch1/sample-app/app.js roles/sample-app/files/Next, create tasks/main.yml with the code shown in Example 9:

- name: Add Node Yum repo (1)

yum_repository:

name: nodesource-nodejs

description: Node.js Packages for x86_64 Linux RPM based distros

baseurl: https://rpm.nodesource.com/pub_23.x/nodistro/nodejs/x86_64

gpgkey: https://rpm.nodesource.com/gpgkey/ns-operations-public.key

- name: Install Node.js

yum:

name: nodejs

- name: Copy sample app (2)

copy:

src: app.js

dest: app.js

- name: Start sample app (3)

shell: nohup node app.js &This code does the following:

| 1 | Install Node.js: This is the same code you used in the Bash script to install Node.js, but translated to use

native Ansible modules for each step. The yum_repository module adds a repository to yum and the

yum module uses that repository to install Node.js. |

| 2 | Copy the sample app: Use the copy module to copy app.js to the server. |

| 3 | Start the sample app: Use the shell module to execute the node binary to run the app in the background. |

To run this playbook, authenticate to AWS, and run the following command:

$ ansible-playbook -v -i inventory.aws_ec2.yml configure_sample_app_playbook.ymlYou should see log output at the end that looks something like this:

PLAY RECAP xxx.us-east-2.compute.amazonaws.com : ok=5 changed=4 failed=0

The value on the left, "xxx.us-east-2.compute.amazonaws.com," is a domain name you can use to access the instance.

Open http://xxx.us-east-2.compute.amazonaws.com:8080 (note it’s port 8080 this time, not 80) in your web

browser, and you should see:

Hello, World!

Congrats, you’re now using a configuration management tool to manage your infrastructure as code!

|

Get your hands dirty

Here are a few exercises you can try at home to go deeper:

|

When you’re done experimenting with Ansible, manually undeploy the EC2 instance as shown in Figure 9.

How Configuration Management Tools Stack Up

Here is how configuration management tools stack up using the IaC category criteria:

- CRUD

-

Most configuration management tools support three of the four CRUD operations: they can create the initial configuration, read the current configuration to see if it matches the desired configuration, and if not, update the existing configuration. That said, support for read and update is a bit hit or miss. It works well for reading and updating the configuration within a server (if you use tasks that are idempotent, as you’ll see shortly), but for managing the servers themselves, or any other type of cloud infrastructure, it only works if you remember to assign each piece of infrastructure a unique name or tag, which is easy to do with just a handful of resources, but becomes more challenging at scale.

Another challenge is that most configuration management tools do not support delete (which is why you had to undeploy the EC2 instance manually). Ansible does support a

stateparameter on most modules, which can be set toabsentto tell that module to delete the resource it manages, but as Ansible does not track dependencies, it’s hard to use it in playbooks with steps that depend on each other. For example, if you updated create_ec2_instances_playbook.yml to setstatetoabsenton theec2_security_groupandec2_instancemodules, and ran the playbook, Ansible would try to delete the security group first and the EC2 instance second (since that’s the order they appear in the playbook), which would result in an error, as the security group can’t be deleted while it’s in use by the EC2 instance. - Scale

-

Most configuration management tools are designed specifically for managing multiple remote servers. For example, if you had deployed three EC2 instances, the exact same playbook would configure all three to run the web server (you’ll see an example of this in Part 3).

- Deployment strategies

-

Some configuration management tools have built-in support for deployment strategies. For example, Ansible natively supports rolling deployments (you’ll see an example of this in Part 3, too).

- Idempotency

-

Some tasks you do with configuration management tools are idempotent, some are not. For example, the

yumtask in Ansible is idempotent: it only installs the software if it’s not installed already, so it’s safe to re-run that task as many times as you want. On the other hand, arbitraryshelltasks may or may not be idempotent, depending on what shell commands you execute. For example, the preceding playbook uses ashelltask to directly execute thenodebinary, which is not idempotent. After the first run, subsequent runs of this playbook will fail, as the Node.js app is already running and listening on port 8080, so you’ll get an error about conflicting ports. In Part 3, you’ll see a better way of running apps with Ansible that is idempotent. - Consistency

-

Most configuration management tools enforce a consistent, predictable structure to the code, including documentation, file layout, clearly named parameters, secrets management, and so on. While every developer organizes their ad hoc scripts in a different way, most configuration management tools come with a set of conventions that makes it easier to navigate and maintain the code, as you saw with the folder structure for Ansible roles.

- Verbosity

-

Most configuration management tools provide a DSL for specifying server configuration that is more concise than the equivalent in an ad hoc script. For example, the Ansible playbooks and role add up to about 80 lines of code, which at first may not seem any better than the Bash script (which was also roughly 80 lines of code), but the 80 lines of Ansible code are doing considerably more: the Ansible code supports most CRUD operations, deployment strategies, idempotency, scaling operations to many servers, and consistent code structure. An ad hoc script that supported all of this would be many times the length.

Configuration management tools brought a number of advantages over ad hoc scripts, but they also introduced their own drawbacks. One big drawback is that some configuration management tools have a considerable setup cost: e.g., you may need to set up master servers and agents. A second big drawback is that most configuration management tools were designed for a mutable infrastructure paradigm, where you have long-running servers that the configuration management tools update (mutate) over and over again, over many years. This can be problematic due to configuration drift, where over time, your long-running servers can build up unique histories of changes, so each server is subtly different from the others, which can make it hard to reason about what’s deployed, and even harder to reproduce the issue on another server, all of which makes debugging challenging.

As cloud and virtualization becomes more and more ubiquitous, it’s becoming more common to use an immutable infrastructure paradigm, where instead of long-running physical servers, you use short-lived virtual servers that you replace every time you do an update. This is inspired by functional programming, where variables are immutable, so after you’ve set a variable to a value, you can never change that variable again, and if you need to update something, you create a new variable. Because variables never change, it’s easier to reason about your code.

The idea behind immutable infrastructure is similar. Once you’ve deployed a server, you never make changes to it again. If you need to update something, such as deploying a new version of your code, you deploy a new server. Because servers never change after being deployed, it’s easier to reason about what’s deployed. The typical analogy used here (my apologies to vegetarians and animal lovers), is cattle vs pets: with mutable infrastructure, you treat your servers like pets, giving each one its own unique name, taking care of it, and trying to keep it alive as long as possible; with immutable infrastructure, you treat your servers like cattle, each one more or less indistinguishable from the others, with random or sequential IDs instead of names, and you kill them off and replace them regularly.

|

Key takeaway #2

Configuration management tools are great for managing the configuration of servers, but not for deploying the servers themselves, or other infrastructure. |

While it’s possible to use configuration management tools with immutable infrastructure patterns, it’s not what they were originally designed for, and that led to new approaches, as discussed in the next section.

Server Templating Tools

An alternative to configuration management that has been growing in popularity recently is to use server templating tools, such as virtual machines and containers. Instead of launching a bunch of servers and configuring them by running the same code on each one, the idea behind server templating tools is to create an image of a server that captures a self-contained "snapshot" of the entire file system. You can then use some other IaC tool to install that image on your servers.

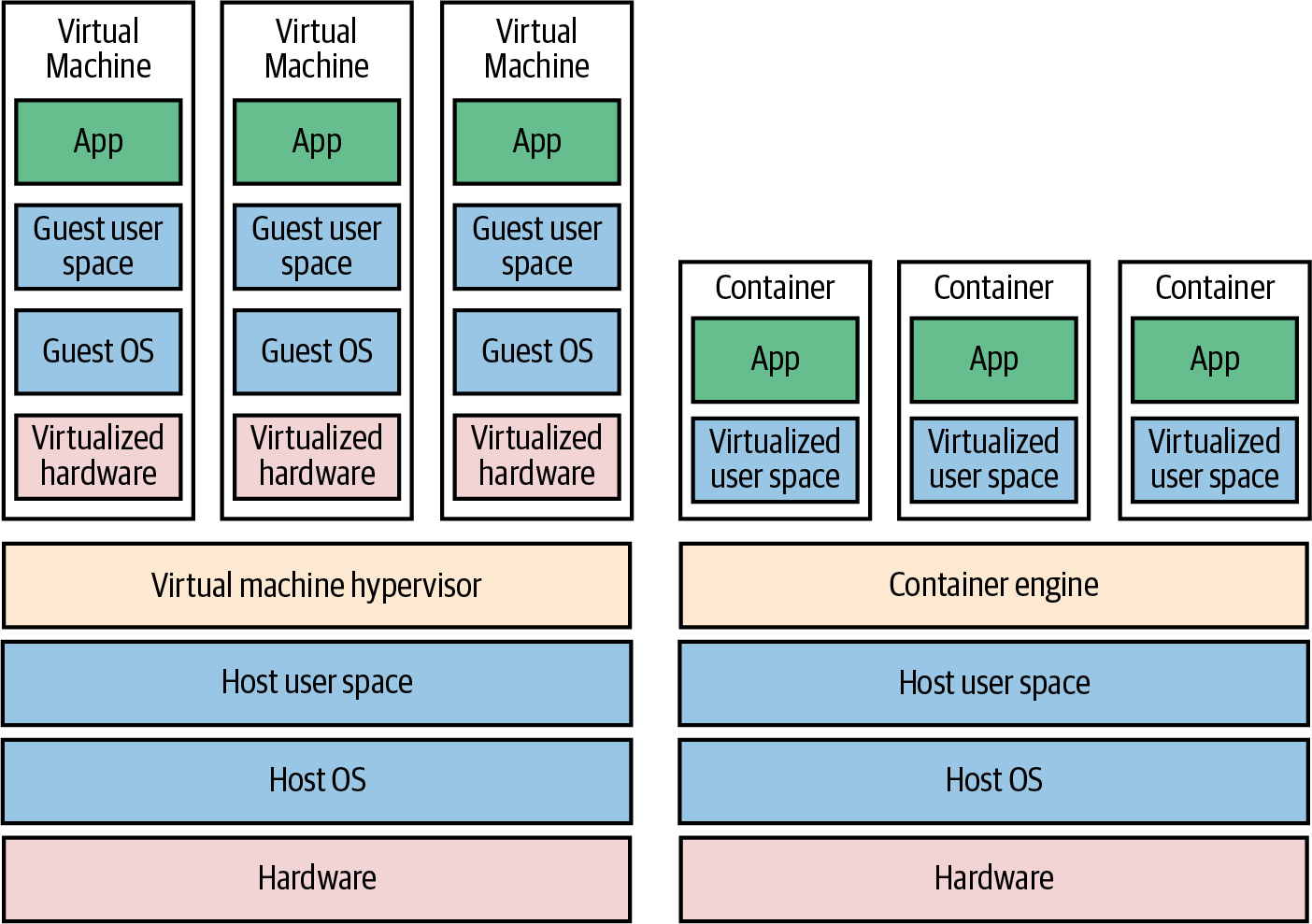

As shown in Figure 19, there are two types of tools for working with images:

- Virtual machines

-

A virtual machine emulates an entire computer system, including the hardware. You run a hypervisor, such as VMware vSphere, VirtualBox, or Parallels (full list), to virtualize (i.e., simulate) the underlying CPU, memory, hard drive, and networking. The benefit of this is that any VM image that you run on top of the hypervisor can see only the virtualized hardware, so it’s fully isolated from the host machine and any other VM images, and it will run exactly the same way in all environments (e.g., your computer, a staging server, a production server). The drawback is that virtualizing all this hardware and running a totally separate OS for each VM incurs a lot of overhead in terms of CPU usage, memory usage, and startup time. You can define VM images as code using tools such as Packer, which you typically use to create images for production servers, and Vagrant, which you typically use to create images for local development.[7]

- Containers

-

A container emulates the user space of an OS.[8] You run a container engine, such as Docker, Moby, or CRI-O (full list), to isolate processes, memory, mount points, and networking. The benefit of this is that any container you run on top of the container engine can see only its own user space, so it’s isolated from the host machine and other containers, and will run exactly the same way in all environments. The drawback is that all the containers running on a single server share that server’s OS kernel and hardware, so it’s more difficult to achieve the level of isolation and security you get with a VM.[9] However, because the kernel and hardware are shared, your containers can boot up in milliseconds and have virtually no CPU or memory overhead. You can define container images as code using tools such as Docker.

You’ll go through an example of using container images with Docker in Part 3. In this blog post, let’s go through an example of using VM images with Packer.

Example: Create a VM Image Using Packer

As an example, let’s take a look at using Packer to create a VM image for AWS called an Amazon Machine Image (AMI). First, create a folder called packer:

$ cd fundamentals-of-devops

$ mkdir -p ch2/packer

$ cd ch2/packerNext, copy the Node.js sample app from Part 1 into the packer folder:

$ cp ../../ch1/sample-app/app.js .Create a Packer template called sample-app.pkr.hcl, with the contents shown in Example 10:

packer {

required_plugins {

amazon = {

version = ">= 1.3.1"

source = "github.com/hashicorp/amazon"

}

}

}

data "amazon-ami" "amazon-linux" { (1)

filters = {

name = "al2023-ami-2023.*-x86_64"

}

owners = ["amazon"]

most_recent = true

region = "us-east-2"

}

source "amazon-ebs" "amazon-linux" { (2)

ami_name = "sample-app-packer-${uuidv4()}"

ami_description = "Amazon Linux AMI with a Node.js sample app."

instance_type = "t2.micro"

region = "us-east-2"

source_ami = data.amazon-ami.amazon-linux.id

ssh_username = "ec2-user"

}

build { (3)

sources = ["source.amazon-ebs.amazon-linux"]

provisioner "file" { (4)

source = "app.js"

destination = "/home/ec2-user/app.js"

}

provisioner "shell" { (5)

script = "install-node.sh"

pause_before = "30s"

}

}You create Packer templates using the HashiCorp Configuration Language (HCL) in files with a .hcl extension. The preceding template does the following:

| 1 | Look up the ID of the Amazon Linux AMI: Use the amazon-ami data source to do the same lookup you saw in the Bash

script and Ansible playbook. |

| 2 | Source images: Packer will start a server running each source image you specify. The preceding code will result in Packer starting an EC2 instance running the Amazon Linux AMI from (1). |

| 3 | Build steps: Packer then connects to the server (e.g., via SSH) and runs the build steps in the order

you specified. When all the build steps have finished, Packer will take a snapshot of the server and shut the

server down. This snapshot will be a new AMI that you can deploy, and its name will be set based on the name

parameter in the source block from (2), which the preceding code sets to "sample-app-packer-<UUID>", where UUID

is a randomly generated value that ensures you get a unique AMI name every time you run packer build. The

preceding example runs two build steps, as described in (3) and (4). |

| 4 | File provisioner: The first build step runs a file provisioner to copy files to the server. The preceding code uses this to copy the Node.js sample app code in app.js to the server. |

| 5 | Shell provisioner: The second build step runs a shell provisioner to execute shell scripts on the server. The preceding code uses this to run the install-node.sh script, which is described next. |

Create a file called install-node.sh with the contents shown in Example 11:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

set -e

sudo tee /etc/yum.repos.d/nodesource-nodejs.repo > /dev/null <<EOF

[nodesource-nodejs]

baseurl=https://rpm.nodesource.com/pub_23.x/nodistro/nodejs/x86_64

gpgkey=https://rpm.nodesource.com/gpgkey/ns-operations-public.key

EOF

sudo yum install -y nodejsThis script is identical to the first part of the Bash script, using yum to install Node.js. More generally, the

Packer template is nearly identical to the Bash script and Ansible playbook, except the result of executing

Packer is not a server running your app, but the image of a server with your app and all its dependencies installed.

The idea is to use other IaC tools to launch one or more servers running that image; you’ll see an example of this

shortly.

To build the AMI, install Packer (minimum version 1.10), authenticate to AWS, and run the following commands:

$ packer init sample-app.pkr.hcl

$ packer build sample-app.pkr.hclThe first command, packer init, installs any plugins used in this Packer template. Packer can create images for

many cloud providers—e.g., AWS, GCP, Azure, etc.—and the code for each of these providers lives in separate plugins

that you install via the init command. The second command, packer build, kicks off

the build process. When the build is done, which typically takes 3-5 minutes, you should see some log output that looks

like this:

==> Builds finished. The artifacts of successful builds are: --> amazon-ebs.amazon_linux: AMIs were created: us-east-2: ami-0ee5157dd67ca79fc

Congrats, you’re now using a server templating tool to manage your server configuration as code! The ami-xxx value is

the ID of the AMI that was created from this template. You’ll see how to deploy this AMI shortly.

|

Get your hands dirty

Here are a few exercises you can try at home to go deeper:

|

How Server Templating Tools Stack Up

How do server templating tools stack up using the IaC category criteria?

- CRUD

-

Server templating only needs to support the create operation in CRUD. This is because server templating is a key component of the shift to immutable infrastructure: if you need to roll out a change, instead of updating an existing server, you use your server templating tool to create a new image, and deploy that image on a new server. So, with server templating, you’re always creating totally new images; there’s never a reason to read, update, or delete. That said, server templating tools aren’t used in isolation; you need some other tool to deploy these images (e.g., a provisioning tool, as you’ll see shortly), and you typically want that tool to support all CRUD operations.

- Scale

-

Server templating tools are highly scalable, as you can create an image once, and then roll that same image out to 1 server or 1,000 servers, as necessary.

- Deployment strategies

-

Server templating tools only create images; you use other tools and whatever deployment strategies those tools support to roll the new images out.

- Idempotency

-

Server templating tools are idempotent by design. Since you create a new image every time, the tool just executes the exact same steps every time. If you hit an error part of the way through, just re-run, and try again.

- Consistency

-

Most server templating tools enforce a consistent, predictable structure to the code, including documentation, file layout, clearly named parameters, and so on.

- Verbosity

-

Since server templating tools usually provide concise DSLs, don’t have to deal with most CRUD operations, and are idempotent "for free," the amount of code you need is typically pretty small.

|

Key takeaway #3

Server templating tools are great for managing the configuration of servers with immutable infrastructure practices. |

As I mentioned a few times, server templating tools are powerful, but they don’t work by themselves. You need another tool to actually deploy and manage the images you create, such as provisioning tools, which are the focus of the next section.

Provisioning Tools

Whereas configuration management and server templating define the code that runs on each server, provisioning tools such as OpenTofu / Terraform[10], CloudFormation, and Pulumi (full list) are responsible for creating the servers themselves. In fact, you can use provisioning tools to create not only servers but also databases, caches, load balancers, queues, and many other aspects of your infrastructure.

Under the hood, most provisioning tools work by translating the code you write into API calls to the cloud provider you’re using. For example, if you write OpenTofu code to create a server in AWS (which you will do in the next section), when you run OpenTofu, it will parse your code, and based on the configuration you specify, make API calls to AWS to create an EC2 instance, security group, etc.

That means that, unlike with configuration management tools, you don’t have to do any extra work to set up master servers or connectivity. All of this is handled using the APIs and authentication mechanisms already provided by the cloud you’re using. Let’s see this in action by going through an example with OpenTofu.

Example: Deploy an EC2 Instance Using OpenTofu

As an example of using a provisioning tool, lets create an OpenTofu module that can deploy an EC2 instance. You write OpenTofu modules in HCL (the same language you used with Packer), in configuration files with a .tf extension. OpenTofu will find all files with the .tf extension in a folder, so you can name the files whatever you want, but there are some standard conventions, such as putting the main resources in main.tf, input variables in variables.tf, and output variables in outputs.tf.

First, create a new tofu/ec2-instance folder for the module:

$ cd fundamentals-of-devops

$ mkdir -p ch2/tofu/ec2-instance

$ cd ch2/tofu/ec2-instanceWithin the tofu/ec2-instance folder, create a file called main.tf, with the contents shown in Example 12:

provider "aws" { (1)

region = "us-east-2"

}

resource "aws_security_group" "sample_app" { (2)

name = var.name

description = "Allow HTTP traffic into ${var.name}"

}

resource "aws_security_group_rule" "allow_http_inbound" { (3)

type = "ingress"

protocol = "tcp"

from_port = 8080

to_port = 8080

security_group_id = aws_security_group.sample_app.id

cidr_blocks = ["0.0.0.0/0"]

}

data "aws_ami" "sample_app" { (4)

filter {

name = "name"

values = ["sample-app-packer-*"]

}

owners = ["self"]

most_recent = true

}

resource "aws_instance" "sample_app" { (5)

ami = data.aws_ami.sample_app.id

instance_type = "t2.micro"

vpc_security_group_ids = [aws_security_group.sample_app.id]

user_data = file("${path.module}/user-data.sh")

tags = {

Name = var.name

}

}The code in main.tf does something similar to the Bash script and Ansible playbook from earlier in the blog post:

| 1 | Configure the AWS provider: OpenTofu works with many providers, such as AWS, GCP, Azure, and so on. This code

configures the AWS provider to use the us-east-2 (Ohio) region. |

| 2 | Create a security group: For each type of provider, there are many different kinds of resources that you can

create, such as servers, databases, and load balancers. The general syntax for creating a resource in OpenTofu is

as follows:

where |

| 3 | Allow HTTP requests: Use the aws_security_group_rule resource to add a rule to the security group from (2) that

allows inbound HTTP requests on port 8080. |

| 4 | Look up the ID of the AMI you built with Packer: Earlier, you saw how to look up AMI IDs in Bash, Ansible, and Packer. Here, you’re seeing the OpenTofu version of an AMI look up, but this time, instead of looking for a plain Amazon Linux AMI, the code is looking for the AMI you built with Packer earlier in this blog post, which was named "sample-app-packer-<UUID>". |

| 5 | Deploy an EC2 instance: Use the aws_instance resource to create an EC2 instance that uses the AMI from (4),

security group from (2), the user data script from user-data.sh, which you’ll see shortly in

Example 13, and sets the Name tag to var.name. |

Create a file called user-data.sh, with the contents shown in Example 13:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

nohup node /home/ec2-user/app.js &Note how this user data script is a fraction of the size of the one you saw in the Bash code. That’s because all the dependencies (Node.js) and code (app.js) are already installed in the AMI by Packer. So the only thing this user data script does is start the sample app. This is a more idiomatic way to use user data.

Next, create a file called variables.tf to define input variables, which are like the input parameters of a function, as shown in Example 14:

variable "name" {

description = "The name for the EC2 instance and all resources."

type = string

}This code defines an input variable called name, which allows you to specify the name to use for the EC2 instance,

security group, and other resources. You’ll see how to set variables shortly. Finally, create a file called

outputs.tf with the contents shown in Example 15:

output "instance_id" {

description = "The ID of the EC2 instance"

value = aws_instance.sample_app.id

}

output "security_group_id" {

description = "The ID of the security group"

value = aws_security_group.sample_app.id

}

output "public_ip" {

description = "The public IP of the EC2 instance"

value = aws_instance.sample_app.public_ip

}The preceding code defines output variables, which are like the return values of a function, which will be printed to the log, and can be shared with other modules. The preceding code defines output variables for the EC2 instance ID, security group ID, and EC2 instance public IP.

Try this code out by installing OpenTofu (minimum version 1.9), authenticating to AWS, and running the following command:

$ tofu initSimilar to Packer, OpenTofu works with many providers, and the code for each one lives in separate binaries that you

install via the init command. Once init has completed, run the apply command to start the deployment process:

$ tofu applyThe first thing the apply command will do is prompt you for the name input variable:

var.name The name for the EC2 instance and all resources. Enter a value:

You can type in a name like "sample-app-tofu" and hit Enter. Alternatively, if you don’t want to be prompted

interactively, you can instead use the -var flag:

$ tofu apply -var name=sample-app-tofuYou can also set any input variable foo using the environment variable TF_VAR_foo:

$ export TF_VAR_name=sample-app-tofu

$ tofu applyOne more option is to define a default value, as shown in Example 16:

variable "name" {

description = "The name for the EC2 instance and all resources."

type = string

default = "sample-app-tofu"

}Once all input variables have been set, the next thing the apply command will do is show you the execution plan

(just plan for short), which will look something like this (truncated for readability):

OpenTofu will perform the following actions:

# aws_instance.sample_app will be created

+ resource "aws_instance" "sample_app" {

+ ami = "ami-0ee5157dd67ca79fc"

+ instance_type = "t2.micro"

... (truncated) ...

}

# aws_security_group.sample_app will be created

+ resource "aws_security_group" "sample_app" {

+ description = "Allow HTTP traffic into the sample app"

+ name = "sample-app-tofu"

... (truncated) ...

}

# aws_security_group_rule.allow_http_inbound will be created

+ resource "aws_security_group_rule" "allow_http_inbound" {

+ from_port = 8080

+ protocol = "tcp"

+ to_port = 8080

+ type = "ingress"

... (truncated) ...

}

Plan: 3 to add, 0 to change, 0 to destroy.

The plan lets you see what OpenTofu will do before actually making any changes, and prompts you for confirmation before

continuing. This is a great way to sanity-check your code before unleashing it onto the world. The plan output is

similar to the output of the diff command that is part of Unix, Linux, and git: anything with a plus sign (+) will

be created, anything with a minus sign (–) will be deleted, anything with both a plus and a minus sign will be

replaced, and anything with a tilde sign (~) will be modified in place. Every time you run apply, OpenTofu will show

you this execution plan; you can also generate the execution plan without applying any changes by running tofu plan

instead of tofu apply.

In the preceding plan output, you can see that OpenTofu is planning on creating an EC2 Instance, security group, and

security group rule, which is exactly what you want. Type yes and hit Enter to let OpenTofu proceed. When apply

completes, you should see log output that looks like this:

Apply complete! Resources: 3 added, 0 changed, 0 destroyed. Outputs: instance_id = "i-0a4c593f4c9e645f8" public_ip = "3.138.110.216" security_group_id = "sg-087227914c9b3aa1e"

It’s the three output variables, including the public IP address in public_ip. Wait a minute or two for the EC2

instance to boot up, open http://<public_ip>:8080, and you should see:

Hello, World!

Congrats, you’re using a provisioning tool to manage your infrastructure as code!

Example: Update and Destroy Infrastructure Using OpenTofu

One of the big advantages of provisioning tools is that they support not just deploying infrastructure, but also

updating and destroying it. For example, now that you’ve deployed an EC2 instance using OpenTofu, make a change to the

configuration, such as adding a new Test tag with the value "update," as shown in

Example 17:

Run the apply command again, and you should see output that looks like this:

$ tofu apply

aws_security_group.sample_app: Refreshing state...

aws_security_group_rule.allow_http_inbound: Refreshing state...

aws_instance.sample_app: Refreshing state...

OpenTofu will perform the following actions:

# aws_instance.sample_app will be updated in-place

~ resource "aws_instance" "sample_app" {

id = "i-0738de27643533e98"

~ tags = {

"Name" = "sample-app-tofu"

+ "Test" = "update"

}

# (31 unchanged attributes hidden)

# (8 unchanged blocks hidden)

}

Plan: 0 to add, 1 to change, 0 to destroy.Every time you run OpenTofu, it records information about what infrastructure it created in an OpenTofu state file. OpenTofu manages state using backends; if you don’t specify a backend, the default is to use the local backend, which stores state locally in a terraform.tfstate file in the same folder as the OpenTofu module (you’ll see how to use other backends in Part 5). This file contains a custom JSON format that records a mapping from the OpenTofu resources in your configuration files to the representation of those resources in the real world.

When you run apply the first time on the ec2-instance module, OpenTofu records in the state file the IDs of

the EC2 instance, security group, security group rules, and any other resources it created. When you run apply again,

you can see "Refreshing state" in the log output, which is OpenTofu updating itself on the latest status of the world.

As a result, the plan output that you see is the diff between what’s currently deployed in the real world and

what’s in your OpenTofu code. The preceding diff shows that OpenTofu wants to create a single tag called Test, which is

exactly what you want, so type yes and hit Enter, and you’ll see OpenTofu perform an update operation, updating the

EC2 instance with your new tag.

When you’re done testing, you can run tofu destroy to have OpenTofu undeploy everything it deployed earlier:

$ tofu destroy

OpenTofu will perform the following actions:

# aws_instance.sample_app will be destroyed

- resource "aws_instance" "sample_app" {

- ami = "ami-0ee5157dd67ca79fc" -> null

- associate_public_ip_address = true -> null

- id = "i-0738de27643533e98" -> null

... (truncated) ...

}

# aws_security_group.sample_app will be destroyed

- resource "aws_security_group" "sample_app" {

- id = "sg-066de0b621838841a" -> null

... (truncated) ...

}

# aws_security_group_rule.allow_http_inbound will be destroyed

- resource "aws_security_group_rule" "allow_http_inbound" {

- from_port = 8080 -> null

- protocol = "tcp" -> null

- to_port = 8080 -> null

... (truncated) ...

}

Plan: 0 to add, 0 to change, 3 to destroy.When you run destroy, OpenTofu shows you a destroy plan, which tells you about all the resources it’s about to

delete. This gives you one last chance to check that you really want to delete this stuff before you actually do it.

It goes without saying that you should rarely, if ever, run destroy in a production environment—there’s no "undo"

for the destroy command. If everything looks good, type yes and hit Enter, and in a minute or two, OpenTofu will

clean up everything it deployed.

|

Get your hands dirty

Here are a few exercises you can try at home to go deeper:

|

Example: Deploy an EC2 Instance Using an OpenTofu Module

One of OpenTofu’s more powerful features is that the modules are reusable. In a general purpose programming language (e.g., JavaScript, Python, Java), you put reusable code in a function; in OpenTofu, you put reusable code in a module. You can then use that module multiple times to spin up many copies of the same infrastructure, without having to copy/paste the code.

So far, you’ve been using the ec2-instance module as a root module, which is any module on which you run apply

directly. However, you can also use it as a reusable module, which is a module meant to be included in other modules

(e.g., in other root modules) as a means of code re-use.

Let’s give it a shot. First, create a folder called modules to store your reusable modules:

$ cd fundamentals-of-devops

$ mkdir -p ch2/tofu/modulesNext, move the ec2-instance module into the modules folder:

$ mv ch2/tofu/ec2-instance ch2/tofu/modules/ec2-instanceCreate a folder called live to store your root modules:

$ mkdir -p ch2/tofu/liveInside the live folder, create a new folder called sample-app, which will house the new root module you’ll use to deploy the sample app:

$ mkdir -p ch2/tofu/live/sample-app

$ cd ch2/tofu/live/sample-appIn the live/sample-app folder, create main.tf with the contents shown in Example 18:

module "sample_app_1" {

source = "../../modules/ec2-instance"

name = "sample-app-tofu-1"

}To use one module from another, all you need is the following:

-

A

moduleblock. -

A

sourceparameter that contains the file path of the module you want to use. The preceding code setssourceto the relative file path of theec2-instancemodule in the modules folder. -

If the module defines input variables, you can set those as parameters within the

moduleblock. Theec2-instancemodule defines an input variable calledname, which the preceding code sets to "sample-app-tofu-1."

If you were to run apply on this code, it would use the ec2-instance module code to create a single EC2 instance.

But the beauty of code reuse is that you can use the module multiple times, as shown in

Example 19:

module "sample_app_1" {

source = "../../modules/ec2-instance"

name = "sample-app-tofu-1"

}

module "sample_app_2" {

source = "../../modules/ec2-instance"

name = "sample-app-tofu-2"

}This code has two module blocks, so if you run apply on it, it will create two EC2 instances, one with all the

resources named "sample-app-tofu-1" and one with all the resources named "sample-app-tofu-2." If you had three

module blocks, it would create three EC2 instances; and so on. And, of course, you can mix and match different

modules, include modules in other modules, and so on. It’s not unusual for modules to be reused dozens or hundreds of

times across a company, so that you put in the work to create a module that meets your company’s needs once, and then

use it over and over again.

Before you run apply, there are two small changes to make. The first change is to move the provider block from the

ec2-instance (reusable) module to the sample-app (root) module, as shown in

Example 20:

provider block (ch2/tofu/live/sample-app/main.tf)provider "aws" {

region = "us-east-2"

}

module "sample_app_1" {

source = "../../modules/ec2-instance"

name = "sample-app-tofu-1"

}

module "sample_app_2" {

source = "../../modules/ec2-instance"

name = "sample-app-tofu-2"

}You typically don’t define provider blocks in reusable modules, and instead inherit those provider configurations

from the root module, which allows users to configure them however they prefer (e.g., use different regions, accounts,

and so on). The second change is to create an outputs.tf file in the sample-app folder with the contents shown in

Example 21:

output "sample_app_1_public_ip" {

description = "The public IP of the sample-app-1 instance"

value = module.sample_app_1.public_ip

}

output "sample_app_2_public_ip" {

description = "The public IP of the sample-app-2 instance"

value = module.sample_app_2.public_ip

}

output "sample_app_1_instance_id" {

description = "The ID of the sample-app-1 instance"

value = module.sample_app_1.instance_id

}

output "sample_app_2_instance_id" {

description = "The ID of the sample-app-2 instance"

value = module.sample_app_2.instance_id

}The preceding code "proxies" the output variables from the underlying ec2-instance module so that you can see

those outputs when you run apply on the sample-app root module. OK, you’re finally ready to run this code:

$ tofu init

$ tofu applyWhen apply completes, you should have two EC2 instances running, and the output variables should show their IPs and

instance IDs. If you wait a minute or two for the instances to boot up, and open http://<IP>:8080 in your browser,

where <IP> is the public IP of either instance, you should see the familiar "Hello, World!" text. When you’re done

experimenting, run tofu destroy to clean everything up again.

Example: Deploy an EC2 Instance Using an OpenTofu Registry Module

There’s one more trick with OpenTofu modules: the source parameter can be set to not only a local file path, but also

to a URL. For example, the blog post series’s sample code repo in GitHub includes an

ec2-instance module that is more or less identical to your own ec2-instance module. You can use the module directly

from the series’s GitHub repo by setting the source parameters to a GitHub URL, as shown in

Example 22:

source to a GitHub URL (ch2/tofu/live/sample-app/main.tf)module "sample_app_1" {

source = "github.com/brikis98/devops-book//ch2/tofu/modules/ec2-instance?ref=1.0.0"

# ... (other params omitted) ...

}The preceding code sets the source URL to a GitHub URL. Take note of two things:

- Double slashes

-

The

sourceURL intentionally includes double slashes (//): the part to the left of the two slashes specifies the GitHub repo and the part to the right of the two slashes specifies the subfolder within that repo. - Ref parameter

-

The

refparameter at the end of the URL specifies a Git reference (e.g., a Git tag) within the repo. This allows you to specify the version of the module to use.

OpenTofu supports not only GitHub URLs for module sources, but

also GitLab URLs, BitBucket URLs, and so on. One particularly convenient option is to publish your

modules to a module registry, which is a centralized way to share, find, and use modules. OpenTofu and Terraform

each provide a public registry you can use for open source modules; you can also run private registries within your

company. I’ve published all the reusable modules in this blog post series to the OpenTofu and Terraform public

registries. Note that the registries have specific requirements on how the repo must be named and its folder structure,

so to publish these reusable modules, I had to copy them to another repo called

https://github.com/brikis98/terraform-book-devops, into the folder structure modules/<MODULE_NAME>, which

allows you to consume the modules using registry URLs of the form brikis98/devops/book//modules/<MODULE>.

For example, instead of the GitHub URL in Example 22, you can use the more convenient

source URL shown in Example 23:

source to a registry URL (ch2/tofu/live/sample-app/main.tf)module "sample_app_1" {

source = "brikis98/devops/book//modules/ec2-instance"

version = "1.0.0"

# ... (other params omitted) ...

}Registry URLs are a bit shorter, and they allow you to use the version parameter to specify the version, which is a

bit cleaner than appending a ref parameter, and supports

version constraints.

Run init on this code one more time:

$ tofu init

Initializing the backend...

Initializing modules...

Downloading registry.opentofu.org/brikis98/devops/book 1.0.0 for sample_app_1...

Downloading registry.opentofu.org/brikis98/devops/book 1.0.0 for sample_app_2...

Initializing provider plugins...The init command is responsible for downloading provider code and module code, and you can see in the preceding

output that, this time, it downloaded the module code from the OpenTofu registry. If you now run apply, you should

get the exact same two EC2 instances as before. When you’re done experimenting, run destroy to clean everything up.

You’ve now seen the power of reusable modules. A common pattern at many companies is for the Ops team to define and manage a library of vetted, reusable OpenTofu modules—e.g., one module to deploy servers, another to deploy databases, another to configure networking, and so on—and for the Dev teams to use these modules as a self-service way to deploy and manage the infrastructure they need for their apps.

This blog post series will make use of this pattern in future blog posts. Instead of writing every line of code from scratch, you’ll be able to use modules directly from this series’s sample code repo to deploy the infrastructure you need for each post.

|

Get your hands dirty

Here are a few exercises you can try at home to go deeper:

|

How Provisioning Tools Stack Up

How do provisioning tools stack up using the IaC category criteria from before?

- CRUD

-

Most provisioning tools have full support of all four CRUD operations. For example, you just saw OpenTofu create an EC2 instance, read the EC2 instance state, update the EC2 instance (to add a tag), and delete the EC2 instance.

- Scale

-

Provisioning tools are highly scalable. For example, the self-service approach mentioned in the previous section—where you have a library of reusable modules managed by Ops and used by Devs to deploy the infrastructure they need—can scale to thousands of developers and tens of thousands of resources.

- Deployment strategies

-

Provisioning tools typically let you use whatever deployment strategies are supported by the underlying infrastructure. For example, OpenTofu allows you to use instance refresh to do a zero-downtime, rolling deployment for groups of servers in AWS; you’ll try out an example of this in Part 3.

- Idempotency

-

Whereas most ad hoc scripts are procedural, where you specify step-by-step how to achieve some desired end state, most provisioning tools are declarative, where you specify the end state you want, and the provisioning tool automatically figures out how to get you from your current state to that desired end state. As a result, most provisioning tools are idempotent by design.

- Consistency

-

Most provisioning tools enforce a consistent, predictable structure to the code, including documentation, file layout, clearly named parameters, and so on.

- Verbosity

-

The declarative nature of provisioning tools and the custom DSLs they provide typically result in concise code, especially considering that code supports all CRUD operations, deployment strategies, scale, and idempotency out-of-the-box. The OpenTofu code for deploying an EC2 instance is about half the length of the Bash code, even though it does considerably more.

Provisioning tools should be your go-to option for managing infrastructure. Moreover, many provisioning tools can be used to not only manage traditional infrastructure (e.g., servers), but many other aspects of software delivery as well. For example, you can use OpenTofu to manage your version control system (e.g., using the GitHub provider), metrics (e.g., using the Grafana provider), and your on-call rotation (e.g., using the PagerDuty provider), tying them all together with code.

|

Key takeaway #4

Provisioning tools are great for deploying and managing servers and infrastructure. |

Although I’ve been comparing IaC tools this entire blog post, the reality is that you’ll probably need to use multiple IaC tools together, as discussed in the next section.

Using Multiple IaC Tools Together

Each of the tools you’ve seen in this blog post has strengths and weaknesses. No one of them can do it all, so for most real-world scenarios, you’ll need multiple tools.

|

Key takeaway #5

You usually need to use multiple IaC tools together to manage your infrastructure. |

The following sections show several common ways to combine tools.

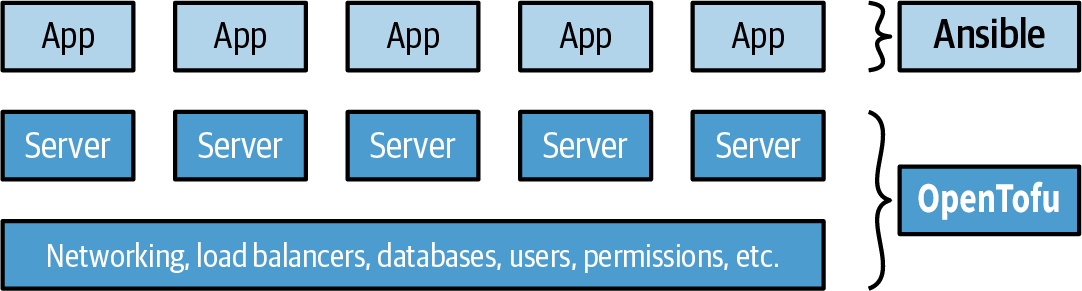

Provisioning Plus Configuration Management

Example: OpenTofu and Ansible. You use OpenTofu to deploy the underlying infrastructure, including the network topology, data stores, load balancers, and servers, and you use Ansible to deploy apps on top of those servers, as depicted in Figure 20:

This is an easy approach to get started with and there are many ways to get Ansible and OpenTofu to work together (e.g., OpenTofu adds tags to your servers, and Ansible uses an inventory plugin to automatically discover servers with those tags). The main downside is that using Ansible typically means mutable infrastructure, rather than immutable, so as your codebase, infrastructure, and team grow, maintenance and debugging can become more difficult.

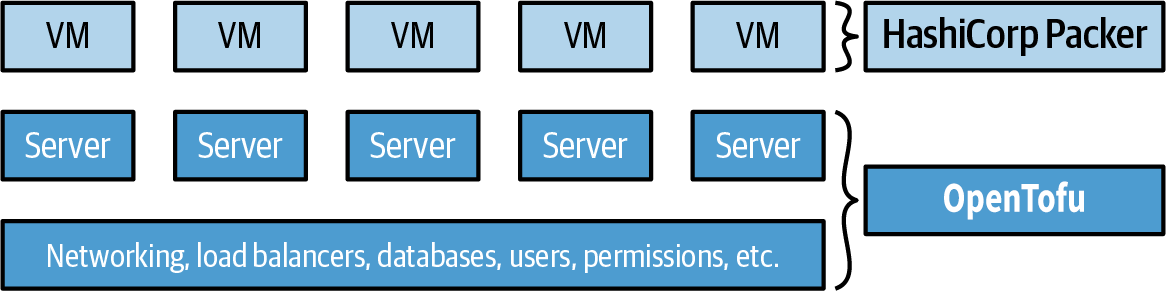

Provisioning Plus Server Templating

Example: OpenTofu and Packer. You use Packer to package your apps as VM images, and you use OpenTofu to deploy your infrastructure, including servers that run these VM images, as illustrated in Figure 21:

This is also an easy approach to get started with. In fact, you already had a chance to try this combination out earlier in this post. Moreover, this is an immutable infrastructure approach, which will make maintenance easier. The main drawback is that VMs can take a long time to build and deploy, which slows down iteration speed.

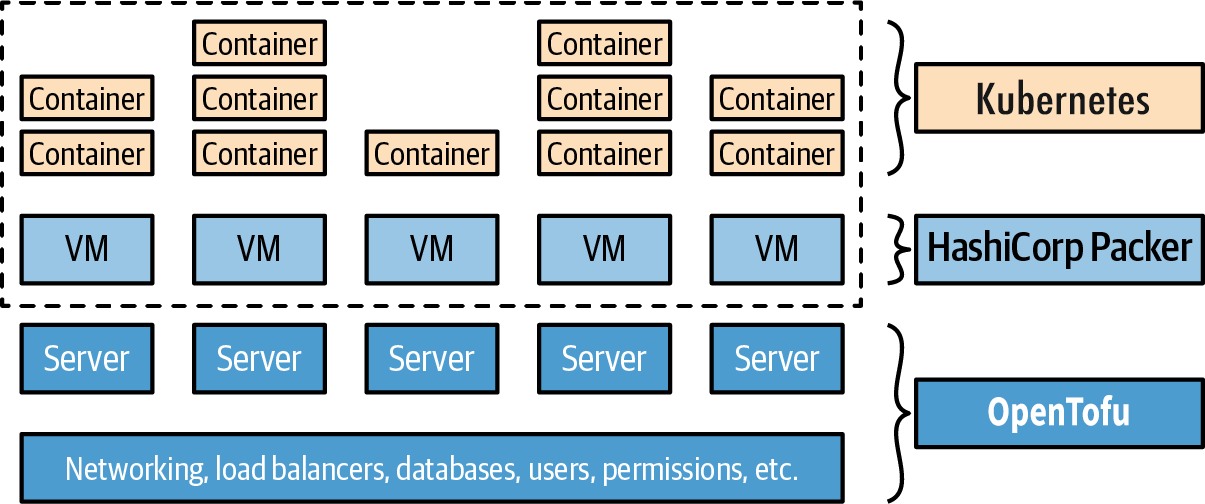

Provisioning Plus Server Templating Plus Orchestration

Example: OpenTofu, Packer, Docker, and Kubernetes. You use Packer to create a VM image that has Docker and Kubernetes installed, you use OpenTofu to deploy your infrastructure, including servers that run this VM image, and when the servers boot up, they form a Kubernetes cluster that you use to run your Dockerized applications, as shown in Figure 22:

You’ll get to try this out in Part 3. The advantage of this approach is that you get the power of an IaC tool (OpenTofu) for managing your infrastructure, the power of server templating (Docker) for configuring your servers (with fast builds and the ability to run images on your local computer), and the power of an orchestration tool (Kubernetes) for managing your apps (including scheduling, auto healing, auto scaling, and service communication). The drawback is the added complexity, both in terms of extra infrastructure to run (the Kubernetes cluster) and in terms of several extra layers of abstraction (Kubernetes, Docker, Packer) to learn, manage, and debug.

Adopting IaC

At the beginning of this blog post, you heard about all the benefits of IaC (self-service, speed and safety, code reuse, and so on), but it’s important to understand that adopting IaC has significant costs, too. Not only do your team members have to learn new tools and techniques, they also have to get used to a totally new way of working. It’s a big shift to go from the old-school sysadmin approach of spending all day managing infrastructure manually and directly (e.g., connect to a server and update its configuration) to the new DevOps approach of spending all day coding and making changes indirectly (e.g., write some code and let an automated process apply the changes).

|

Key takeaway #6

Adopting IaC requires more than just introducing a new tool or technology: it also requires changing the culture and processes of the team. |

Changing culture and processes is a significant undertaking, especially at larger companies. Because every team’s culture and processes are different, there’s no one-size-fits-all way to do it, but here are a few tips that will be useful in most situations:

- Adapt your architecture and processes to your needs

-